To commemorate 16 Days of Activism Against Gender-Based Violence 2022, Gender Talk 211 highlighted 16 individual and collective South Sudanese women and girls’ stories of resistance (a story each day) to 16 forms of GBV under the theme “UNITE: Activism to End Violence against Women & Girls!”

- Historical Use Of Radio As An Effective Tool For Resistance

During the liberation movement, Radio SPLA was the main radio amplifying voices of South Sudanese and the resistance during the struggle. One voice often stood out, Hon. Rebecca Joshua’s. As a young journalist and woman on the frontlines, Rebecca Joshua used the media as a tool to join the liberation fight against the Khartoum regime. She became known as the “Voice of the Revolution.” Presently, South Sudanese women journalists continue to use media, specifically radio, as a tool to fight for women’s rights, especially against violence against women and girls. Veteran Journalist Mama Hellen hosts “Peace of Her Mind” on Eye Radio Juba; Irene Lasu remains a voice for women on Radio Miraya’s “The Breakfast Show” and our own Gender Talk 211 on Advance Youth Radio. Radio is one of the oldest forms of resistance passed on from generation to generation to mobilize and amplify women’s voices and struggles in South Sudan.

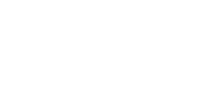

2. Resisting Child and Forced Marriage

In Dec 2020, Abuk Lual sued her parents for attempting to force her into marriage. Abuk reported to a police station in the town of Aweil, accusing her parents of initiating an arranged marriage having realized her family received 16 cattle in exchange for her hand in marriage. “Since I opened the case, I have been disowned by my relatives and now staying at the police station.” said the 16-year-old as she appealed to the public in an emotional statement. Child and forced marriages are common within the South Sudanese communities and of recently been used as a poverty survival transaction. The South Sudan Child Act 2008 deems child marriages a criminal act punishable by law. However, South Sudan has yet to witness a just indictment against enforcers of child marriages across the country. Abuk’s bravery has shown many South Sudanese girls that there are different ways to resist forced and child marriage.

3. South Sudan Women’s Silent March

December 9, 2017, South Sudanese women from different walks of life came out in numbers and silently marched with their mouths taped while holding up placards with powerful messages of condemnation of sexual and gender-based violence, the war, injustices, and all kinds of violence and abuse perpetrated by both individuals and the state that affected primarily women and girls. The women marched to their final destination, a church for the second part of the March, where they conducted “prayers for Peace.” In South Sudan, assembly and demonstrations are constitutional rights. However, citizens are demanded to seek authorization from National Security Service to exercise this right. Even though the organizers had acquired the needed security clearance to hold their silent March and prayers for peace, National Security officers still showed up at the church, requesting the event to be shut down & two organizers to be taken in for questioning because the women were authorized to silently March, not hold up placards with the kinds of messages they had. The organizers braved the harassment during the prayers and ensured the women inside the church completed the prayers. The organizers were called in for a series of interrogation days after the March, but that never stopped South Sudanese women and girls from protesting & marching on the streets of Juba to demand accountability & justice for gender-based crimes.

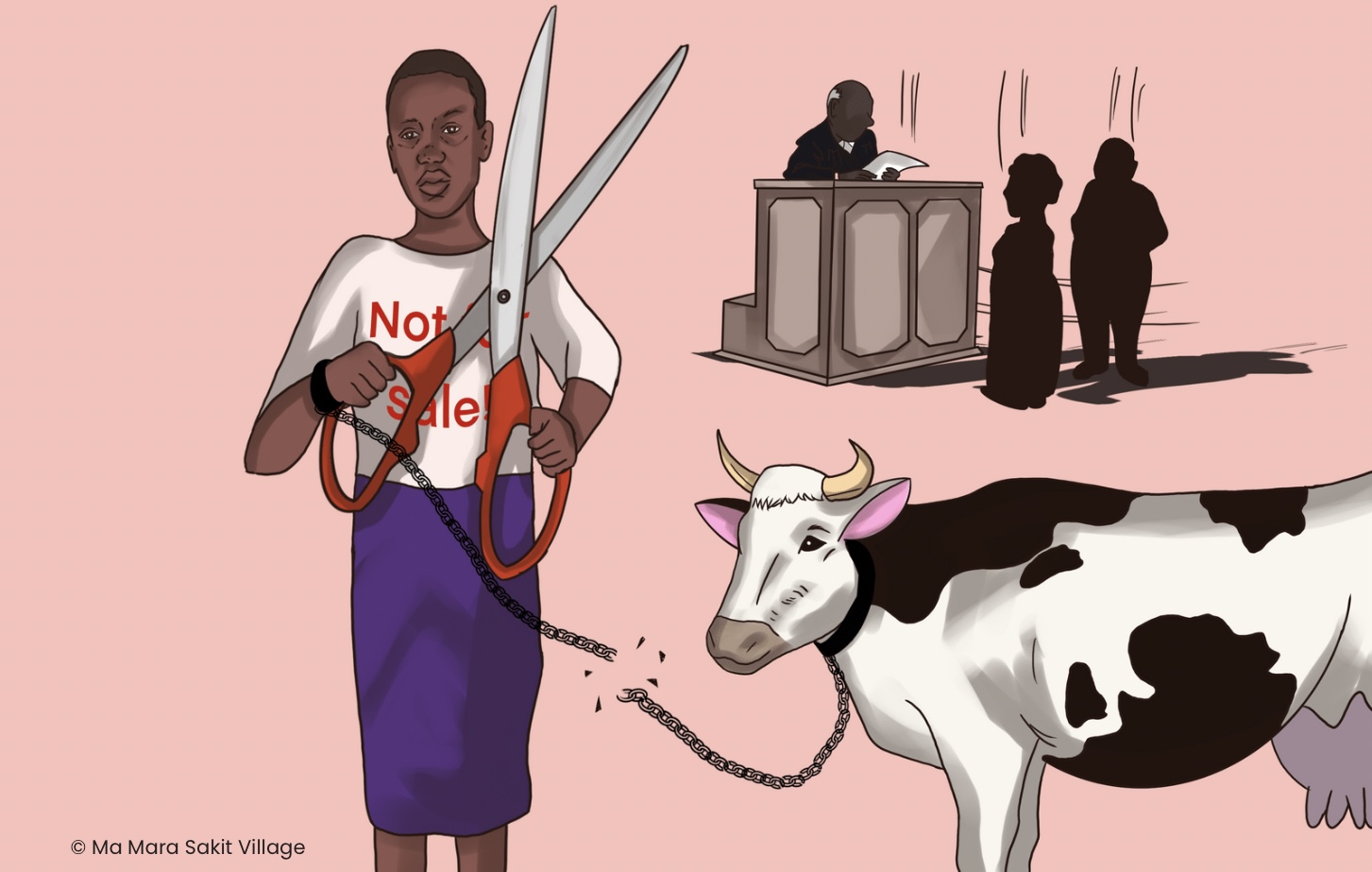

4. Fighting For The Most Basic Right, Education

“I believe that if restrictions were not applied in Girls’ Education in the south, many of them would have gone to University. Girls were not allowed to progress” – Victoria Yar, 1979. Victoria Yar was South Sudan’s first woman university graduate and the South’s (then Sudan) most distinguished and tireless campaigner for girls’ education. In the process breaks many gender/social stereotypes. Yar used education as a vehicle for gender equality in a society that prioritized marriage in a girl’s life and took away her rights to childhood and choice. Later in her life, Yar used her position as a member of parliament to promote women’s rights and education. Today, we’ve witnessed progress through time, yet the narrative isn’t much different. Culture and poverty continue to prioritize marriage over a girl’s education. In recent years, child and forced marriages have steadily increased. Women have also adapted to new forms of resistance to ensure girls’ education. We are grateful for women like Yar and many other South Sudanese women who fought for this right that has benefited many of us today.

5. Bodily Autonomy and Career Choices

In the 1990s, Supermodel Alek Wek dominated runways abroad, paving a career path for aspiring South Sudanese models from a country that commodifies and controls women’s bodies and choices. Today the presence of South Sudanese models in the industry is notable through Adut Akech, Anok Yai, Duckie Thot, and many more. While this is celebrated locally for its international status, the models are subjected to objectification and slut-shaming for their work. Moreover, local aspiring models are subjected to the same at a heightened intensity for not having an international status which seems to provide a certain amount of justification for their choice of work.

Despite these community push-backs, South Sudanese models continue to rise and remain booked and busy. We’ve also seen a steady rise in young girls and women joining the industry to pursue their dreams. Winning is the most fierce form of resistance.

6. #SouthSudanSurvivor

One of the South Sudanese online’s most powerful moments on Social Media was the unexpected #SouthSudaneseSurvivor. In June 2020, South Sudanese women in Australia, followed by the United States, started sharing their stories and experiences of sexual harassment, abuse, assault, and rape by particularly South Sudanese women. Many young women came out and bravely named their abusers.

The stories described some of the most gruesome details of South Sudanese women and girls’ experiences across the globe. For the first time, South Sudanese on Twitter openly discussed terms such as “consent” and “No means No.” Older South Sudanese women, especially on Facebook, stood in solidarity by hosting discussions through Facebook live, while others appreciated the young women for breaking the silence. While the survivors received support, they received threats and were harassed for namingtheir abusers. #SouthSudaneseSurvivor remains one of South Sudanese women’s most outstanding digital resistance.

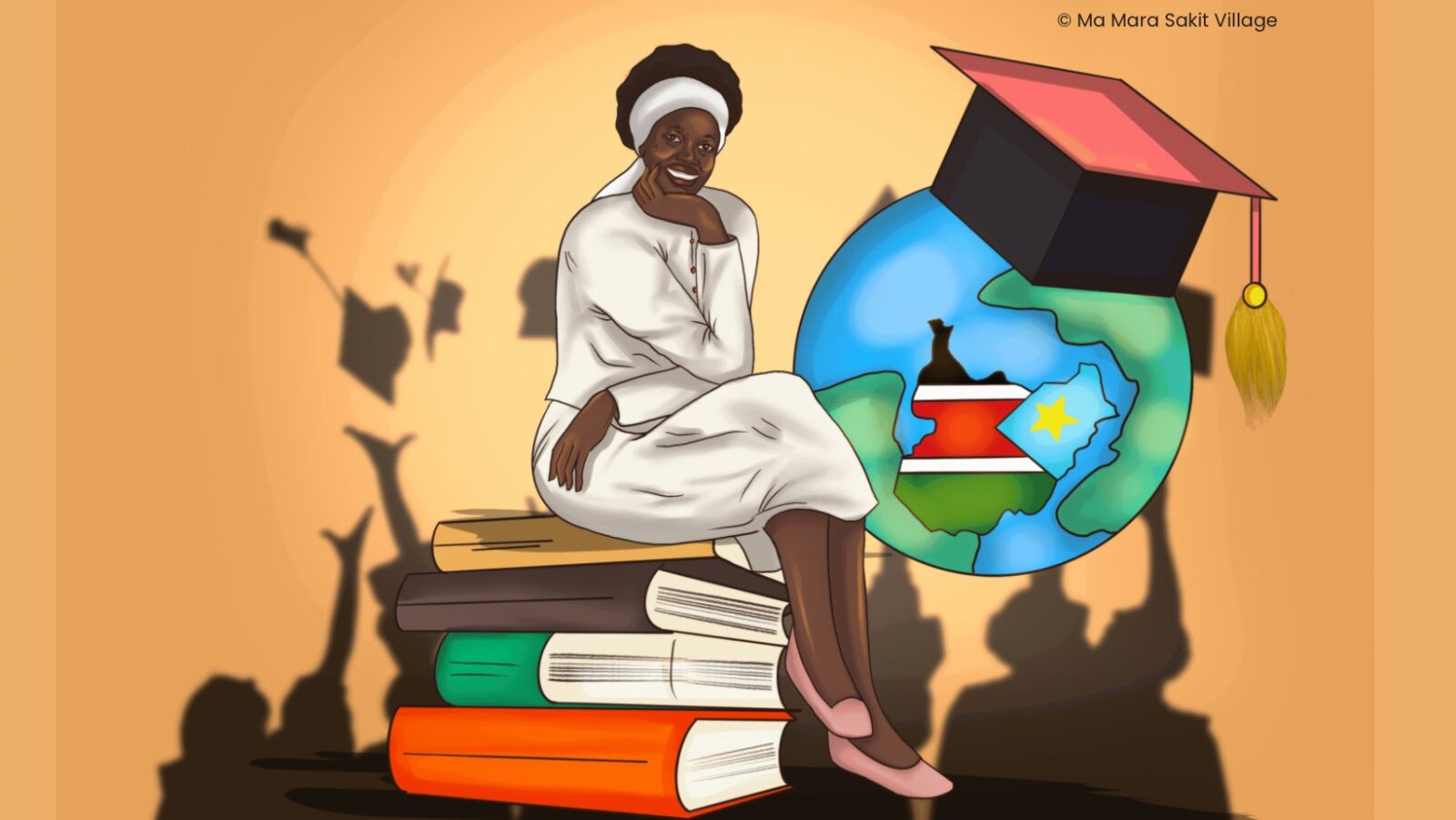

7. Changing The Narrative, Telling South Sudanese Women’s Stories Globally

Despite so much talent and interest from the youth, the South Sudan film industry remains underdeveloped due to various reasons not limited to war and lack of funding. Films shape narratives, cultural attitudes, and customs. Like many African countries, especially those affected by war, South Sudan’s global description is very negative, especially women and girls’ stories told from solely “victimhood narratives” by others. Early this year, the new film “No Simple Way Home’ directed by Akuol de Mabior, a young South Sudanese filmmaker, came out. A film that centers on an intergenerational discourse that charts the three women’s struggle to reconcile family and country; the mother’s mission to safeguard her late husband’s vision while her daughters struggle with what it means to call South Sudan home. This film is the first of its kind in South Sudan, a big shoutout to Akuol. It’s always exciting to see young South Sudanese women take the leading and change narratives. We will tell 16 individual and collective South Sudanese women and girls’ stories of resistance.

8. The Use Of Art To Unchain Silenced, Powerful Voices.

Art has always been one of the most powerful tools used by South Sudanese women and girls across cultures for activism and resistance. Women and girls express themselves through music, spoken word, poetry, storytelling, painting, pottery, bead-making, crocheting & embroidery, among other forms. In 2019 Abul Oyay, a curator, painter, and artist, established the Baobab Arts Foundation in Juba. The space where she works equally acts as a gallery where she showcases her work and the work of various South Sudanese artists: she hosts shows, exhibitions, and other events. Abul uses herself as the subject to explore and present the battle between societal expectations and what she wants, something every South Sudanese woman can relate to. She takes women from all walks of life through self-discovery, expression, and love.

9. Feminist Cybersecurity

Image-based sexual abuse is the newest form of sexual abuse against women in South Sudan. Time after time, we’ve woken up to receive a notification leading to a viral video of a woman’s vulnerable and private moments shared with the public without her consent to humiliate, blackmail, and as a form of punishment. Often by one’s partner. Although we’ve witnessed the tactic used against men, women are the most common victims. The practice is described as a form of psychological abuse, domestic violence, and sexual abuse. Women in Tech in South Sudan have taken up a role in capacity building and raising awareness to safeguard women and girls online. In addition to advocating for the criminalization of Image-based sexual abuse and introducing cyber laws that combat the practice and protect women and girls online.

10. The Katiba Banat

“We fought for this country” is a statement South Sudanese say a lot to express what it took to have an independent South Sudan from Sudan. A legacy of military resistance that can be traced back to 1955. When the Sudan People’s Liberation Army/Movement, the movement that eventually led the people of Southern Sudan to an independent state, was formed in 1983, a group of girls that later came to be known as the “Katiba Banat” meaning “ the Girls’ Battalion” joined the army and were at frontlines with their male counterparts. To call them women is adultification because these were mostly girls in their late teens and early 20s. The story of the Katiba Banat is one of South Sudan’s historical feminist acts, not only because they joined an armed movement fighting for liberation but because of the layers of patriarchal norms they dismantled. These were mostly girls in school when girls’ education was taboo in their communities, which was a form of resistance. Their action later inspired other out-of-school girls & young women to join the movement. These girls came from communities where it was unheard of for girls to leave their homes & go far away “unsupervised” by brothers or male relatives. While we celebrate them today, These girls & young women were stigmatized, slut-shamed, and called all kinds of names for simply joining the liberation movement like their male counterparts.

11. Resisting The Policing Of Women And Girls Bodies In Bor

In 2021 media houses reported a police crackdown on young women and girls for wearing “indecent clothes” in Jonglei state. Some of the victims interviewed shared that they were stripped naked and their clothes burnt, harassed, beaten, and even illegally detained for wearing trousers or outfits “considered” short or tight. The National Alliance for Women Lawyers and Sisterhood Solidarity condemned this illegal act and demanded accountability, but the harassment continued. In April 2022, a young woman named Yar Ayuen took to social media to share her experience of being harassed on her way to work by security officers on the grounds of “indecent dressing.” Her story sparked social media outrage, with more voices condemning the act. Yar was arrested and detained on the orders of the Brigadier General, who heads the Joint Operation Unit that spearheaded this crackdown with endorsement from the county paramount chief. He opened a “defamation” court case against her for sharing her experience on social media. Yar stood her ground and took the issue head-on with support from her family, Sisterhood Solidarity, and many other South Sudanese voices across the globe. Yar was later released, and the member of parliament representing Twic East County of Jonglei State called the Inspector General of the Police to investigate the head of joint operations in Bor town for allegedly harassing women over a dress code. There haven’t been any reports of harassment over the dress code in Jonglei state since Yar’s fierce actions.

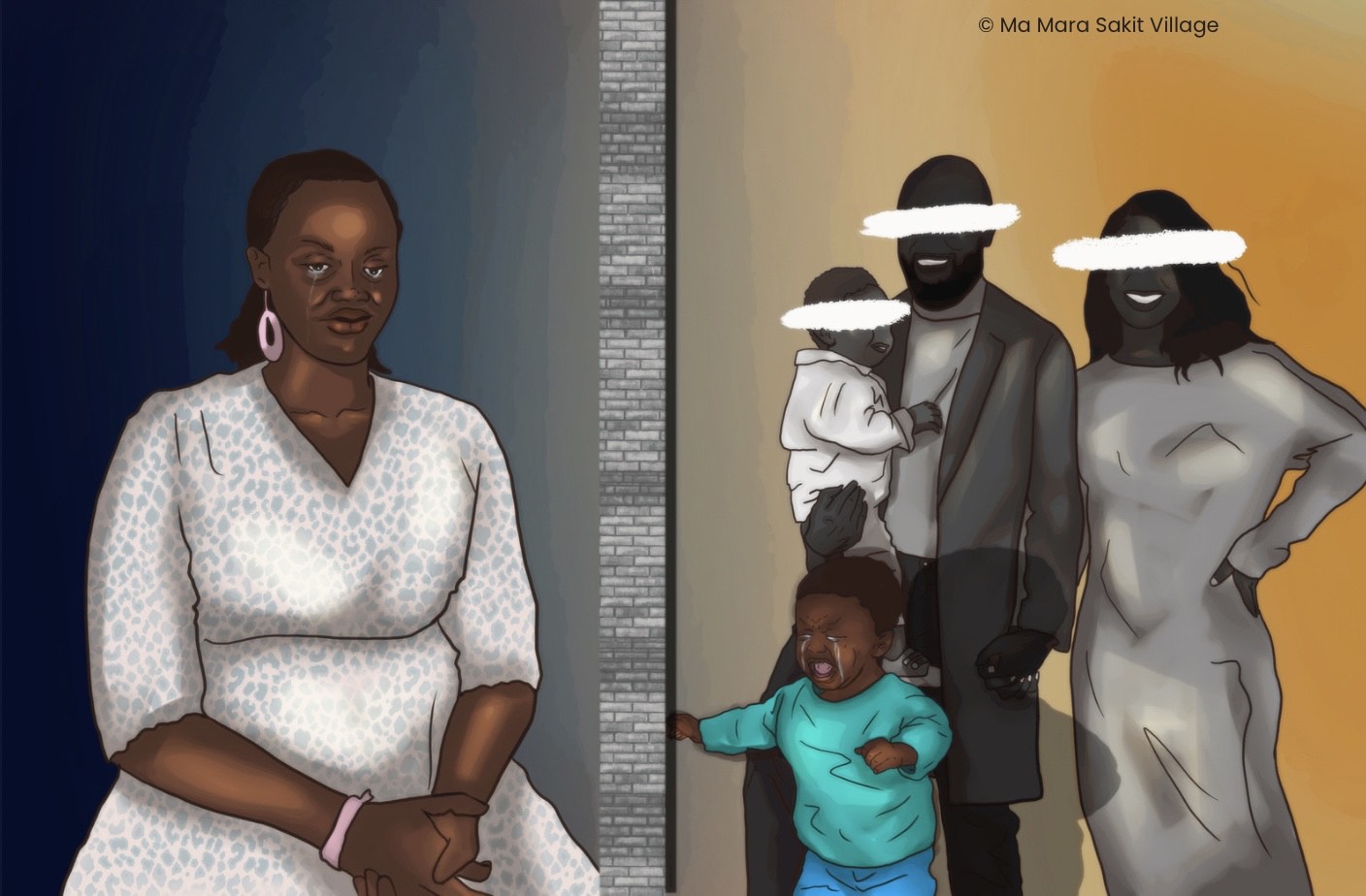

12. Fruits Of My Womb and Labor That I Have No Rights To (Child Custody Battles)

In march 2022, Yar Makuei shared a brief video on her struggle and legal battles against her ex-husband as she fought for access to her children. According to Yar, she married her now ex-husband in 2008. They had four children but lost one in a tragic incident in 2020. She lives with only one of their children, a young boy with autism, while the rest reside with the father and his new wife in Mombasa. The video mainly focused on her struggle with being prevented from seeing her children.Yar appealed to the public for emotional and legal support to continue fighting to gain access to her children. While her story received immense support from the public, it was also met with threats and resistance for publicizing a “family matter” and speaking up. This story gained so much public attention, but this was not the first story of a children-custody battle to go viral on South Sudanese social media; in 2021, Aman Bol, the wife to one of the prominent Dinka singers Diinganyai, went on Facebook live to share the harassment and abuse she was being subjected to in the process of fighting for her children’s custody, a case she later won in court. Yar’s story opened so many conversations amongst South Sudanese women globally who share or could relate to her pain and women resisting cultural and societal norms that 1. Do not believe in divorce, 2. Strongly believe in “Children belong to the father,”, especially after a divorce. Many women’s hopes lie in the GBV Bill that is yet to be passed by parliament, a Bill that is a good starting point to addressing some of these issues, and the Family Law that some women’s rights organizations are still working on and trying to push through.

13. Marriage Is Not A Death Sentence For Women

In 2021, Viola Riak, a feminist activist and one of the most prominent women’s rights advocates in South Sudan, came out and said I am a survivor of GBV and have been in an abusive marriage for the past ten years. She did not only come out to share her story, debunking the myths many South Sudanese hold about GBV, showing that no level of independence can fully protect any woman from patriarchal violence, but she was also one of the first women to share updates of her divorce in real-time, a process many women are stigmatized for. While many women stood in solidarity with her, many others came out to talk about the abuses they are silently experiencing in their marriages. Still, as expected, many men condemned, insulted, and called her names because nothing shakes the patriarchy like a woman who can’t be controlled or shamed anymore. “There are so many women in abusive marriages, and they tolerate it because they are afraid of what society will say. They are afraid that, if they walk out of marriages, the kids will be taken away from them. They are afraid that if they walk away and are not educated, they will not be able to support themselves and their children”, she said in one of her interviews. For many South Sudanese women married with bride price, exiting these marriages is one of the hardest things, no matter how deadly they get. South Sudan is still far from achieving equality, especially in marriage. Still, women’s rights organizations and feminist activists are working tirelessly for the country to have family law and GBV Act, and brave acts like Viola’s are a great foundation for these efforts.

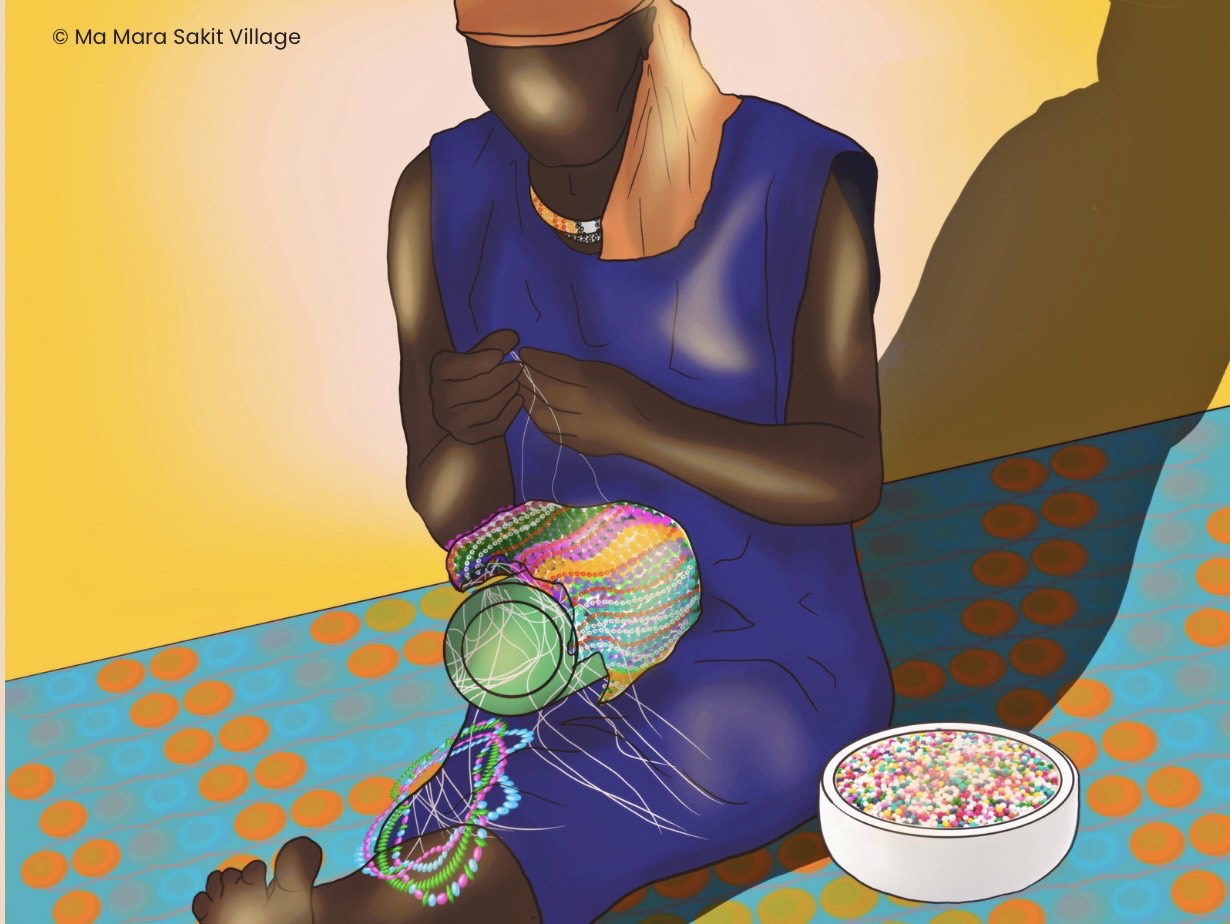

14. Women And Girls Preserving Cultural Heritage

South Sudanese women and girls play a significant role in maintaining cultural heritage, but like many things women do, this often goes unnoticed or unrecognized. As South Sudan transitions to modern days along with the world, many positive, unifying,and fundamental parts of our cultures, such as bead-making, are slowly dying in urban and semi-urban settings as they largely remain done by older women. Beaded accessories are a big part of South Sudanese culture and are purposefully color-coded to indicate one’s age group or status, cultural beliefs, and expressions. Roots of South Sudan, a nonprofit organization, has been working tirelessly to empower women and youth and actively contributing to preserving South Sudanese arts and crafts, especially beadwork, since 2011. Their work inspired other women interested in expounding this work, such as the Suk-Sukna Women and Girls Beadmakers and other women groups in urban and semi-urban areas doing beadwork. To ensure beadmaking skills and knowledge are adequately passed on to the next generation while making the beads more accessible and affordable to South Sudanese, particularly within urban local cultural contexts and communities.

15. Economic Independence

Many South Sudanese women have broken free from the patriarchal captivity of only working in homes, providing unpaid domestic and care work. They are out in the markets selling products and vegetables; they are on every corner of the streets as vendors, doing subsistence farming to provide for their families. Primarily self-employed, carrying the country’s economy on their backs while working under unimaginable conditions. But often, when we think about women entrepreneurs, these women aren’t the ones that pop up in people’s minds. Economic justice and rights, especially equitable access and control of the productive family and communal resources, are still a work in progress in South Sudan. Still, these women continue to show us daily that they will not back down. While we recognize these women’s resistance, South Sudanese feminist activists and organizations still have much work to ensure equal redistribution of domestic and care work, with more women working outside of homes as sole breadwinners or equally providing for their families. It is not equality if women are providing and still shouldering the burden of providing domestic and care work.

16. Defying The Gender Binary

Simply existing in a homophobic, transphobic, biphobic, and patriarchal world as a South Sudanese lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, & queer person is the highest form of resistance. Just because their identities are criminalized, and many are forced to live in hiding doesn’t mean we don’t have lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and non-conforming South Sudanese. We have seen the level of homophobia and transphobia the few South Sudanese who have dared to go public about their sexuality have been subjected to. Still, they have no option but to fight back because sexuality is not a “choice” people make that they can snap out of. There is no hierarchy of rights or justice; we can’t speak liberation for women and girls if we fail to see and make our struggle holistic and inclusive of the rights of other sexual and gender-minoritized South Sudanese groups.